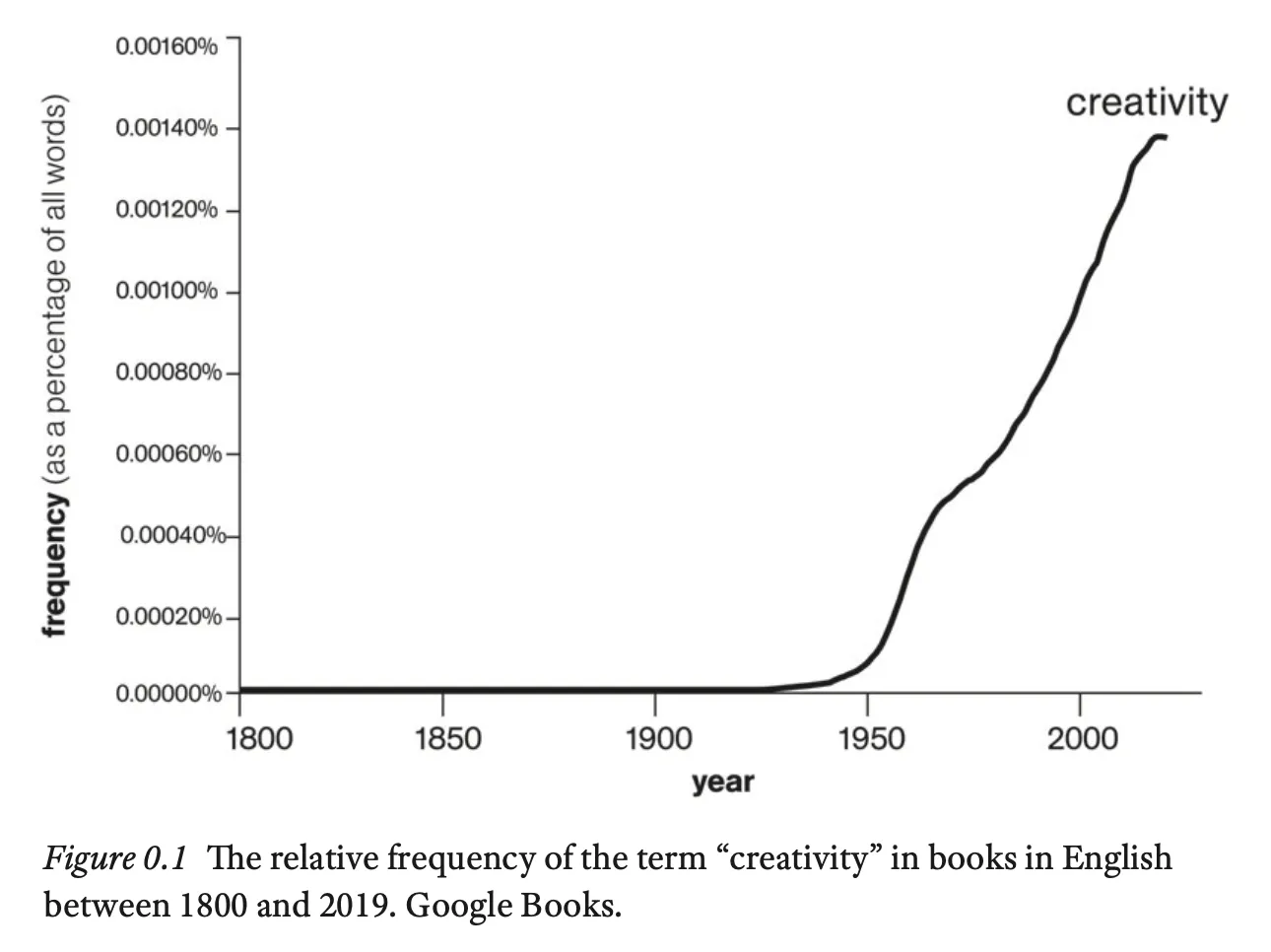

‘Creëeren’ en ‘creatie’ zijn natuurlijk oude woorden maar ‘creativiteit’ als naam voor een persoonlijke eigenschap of een mentale eigenschap is volgens schrijver Samuel W. Franklin een fenomeen dat pas in de Koude Oorlog ontstaan is.

Ik las niet dat boek, The Cult of Creativity, maar de geweldige longread die The New Yorker erover schreef.

Het stuk vertrekt vanuit de vraag wat creative nonfiction nu precies is.

One definition of “creative nonfiction,” often used to define the New Journalism of the nineteen-sixties and seventies, is “journalism that uses the techniques of fiction.” But the techniques of fiction are just the techniques of writing. You can use dialogue and a first-person voice and description and even speculation in a nonfiction work, and, as long as it’s all fact-based and not make-believe, it’s nonfiction.

Het is een term die voor mij sterk verbonden is aan de Amerikaanse schrijver Gay Talese. De man werd ondermeer bekend door zijn stuk Sinatra Has a Cold. Een stuk waarin Sinatra nauwelijks aan het woord komt omdat deze, vanwege een verkoudheid, niet met Gay wilde praten. In plaats daarvan bleef Gay rondhangen in de buurt van Sinatra en observeerde hem en zijn entourage.

Het stuk leest als literatuur maar is non-fictie. In de documentaire Voyeur (te zien op Netflix) wordt de werkwijze van Gay Talese blootgelegd. Wat blijkt? Gay verzint niets, alles is precies zo gegaan zoals hij beschrijft.

Het lijkt een contradictie om het opschrijven van feiten als iets creatiefs te bestempelen. Want creativiteit draait immers toch om ‘iets nieuws verzinnen’?

Making something new, original, and surprising is what is meant by being creative, and a better mousetrap qualifies. What about creating something new, original, and terrible, like a weapon of mass destruction?

Kortom: ook voor het bedenken van verschrikkelijke dingen moet je beschikken over creativiteit.

In het boek The Cult of Creativity beschrijft Franklin dat tijdens de Koude Oorlog er de angst heerste dat de Russen een technologische voorsprong op het Westen hadden. En dat daarom een beroep werd gedaan om tot creatieve oplossingen te komen. Brainstormsessies kwamen van de grond en er werd een duidelijk onderscheid gemaakt tussen de witte boorden die creatief mochten denken en blauwe boord-werkers die niet vrij mochten denken maar slechts moesten uitvoeren.

The belief was that this was how creative people, like artists and poets, came up with new stuff. They needed to be liberated from organizational regimens. So workers played at being artists. Dress was informal; sessions were held in relaxed settings designed to look like living rooms; conversation was casual (though someone was taking notes). The idea was not to accomplish tasks. The idea was to, essentially, make stuff up.

Maar waarom is de ene persoon creatief en de ander niet?

Uncreative people are rigid and repressed; creative people are authentically themselves, and therefore fully human. As the psychologist and popular author Rollo May put it, creativity is not an aberrant quality, or something associated with psychic unrest—the tormented-artist type. On the contrary, creativity is “the expression of normal people in the act of actualizing themselves.” It is associated with all good things: individualism, dignity, and humanity. And everyone has it. It just needs to be psychically unlocked.

Kijk, nu wordt het interessant! Met name die zin ‘creativity is not an aberrant quality, or something associated with psychic unrest—the tormented-artist type’. Creativiteit heeft in essentie dus helemaal niets te maken met ‘psychische onrust – het gekwelde kunstenaarstype.’ Dat heb ik zelf ook altijd zo gezien. Ik maak me nog altijd boos wanneer de kunstenaar als geniale gek wordt gezien. Met vaak als voorbeeld: Vincent van Gogh. Vincent was geen groot kunstenaar door zijn geestesziekte maar ONDANKS die geestesziekte.

Als je kijkt naar onze huidige maatschappij dan wordt creativiteit bij witte boord-denkers maximaal gestimuleerd en beloond. Het bedrijfsleven richt zich op innovatie en dat vraagt dus om creativiteit. Onze computers, webtechnologie, apps, social media, ze komen allemaal voort uit creatieve denkprocessen.

The landscape of the tech universe is shifting right now, but for several decades a whole creativity life style became associated with it. Work was play and play was work. Coders dressed like bohemians. Business was transacted (online) in cafés, where once avant-gardists had sipped espresso and shared their poems. “The star of this new economy,” Franklin writes, was “the hip freelancer or independent studio artist, rather than the unionized musician or actor who had been at the heart of the cultural industries.” In his view, this is perfectly natural, since “creativity” was an economic, not aesthetic, notion to begin with. “The concept of creativity,” he concludes, “never actually existed outside of capitalism.”

Laat dat even inzinken: het concept creativiteit heeft dus eigenlijk nooit bestaan buiten het kapitalisme.

Creating things today seems to be as cool as it ever was. Fewer college students may be taking literature courses, but creative-writing courses are oversubscribed. And what do those students want to write? Creative nonfiction.

Geef een reactie